By Srinath Rengarajan, Automotive Expert at Oliver Wyman

Across all major automotive markets globally, we are witnessing a transformative shift to electric mobility. Even during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, while vehicle sales have dropped significantly in many of these markets, the uptake of electric vehicles have bucked the trend in 2020. Their role in decarbonizing the transport and mobility sector is firmly established through compelling arguments from efficiency, carbon footprint, and total cost of ownership perspectives. With an eye on meeting its climate targets, improving air quality, reducing the reliance on imported oils, and exploiting its energy surplus with an increasing renewable share in the mix, India is keen to follow this global trend.

At the heart of the shift towards a green society powered by clean energy, advanced battery technologies play a pivotal role. In EVs, batteries are not only the energy storage medium, but also crucial for determining performance, ensuring reliability, and gaining customer acceptance across metrics including costs, vehicle range, and charging speeds. Beyond e-mobility, they are also an important cog in the energy sector as stationary storage for applications like grid balancing and for power generated from renewable sources like wind or solar. Despite their importance, however, India has been largely reliant on importing battery cells from east Asia with limited local module and pack assembly operations so far.

Need for Local Gigafactories

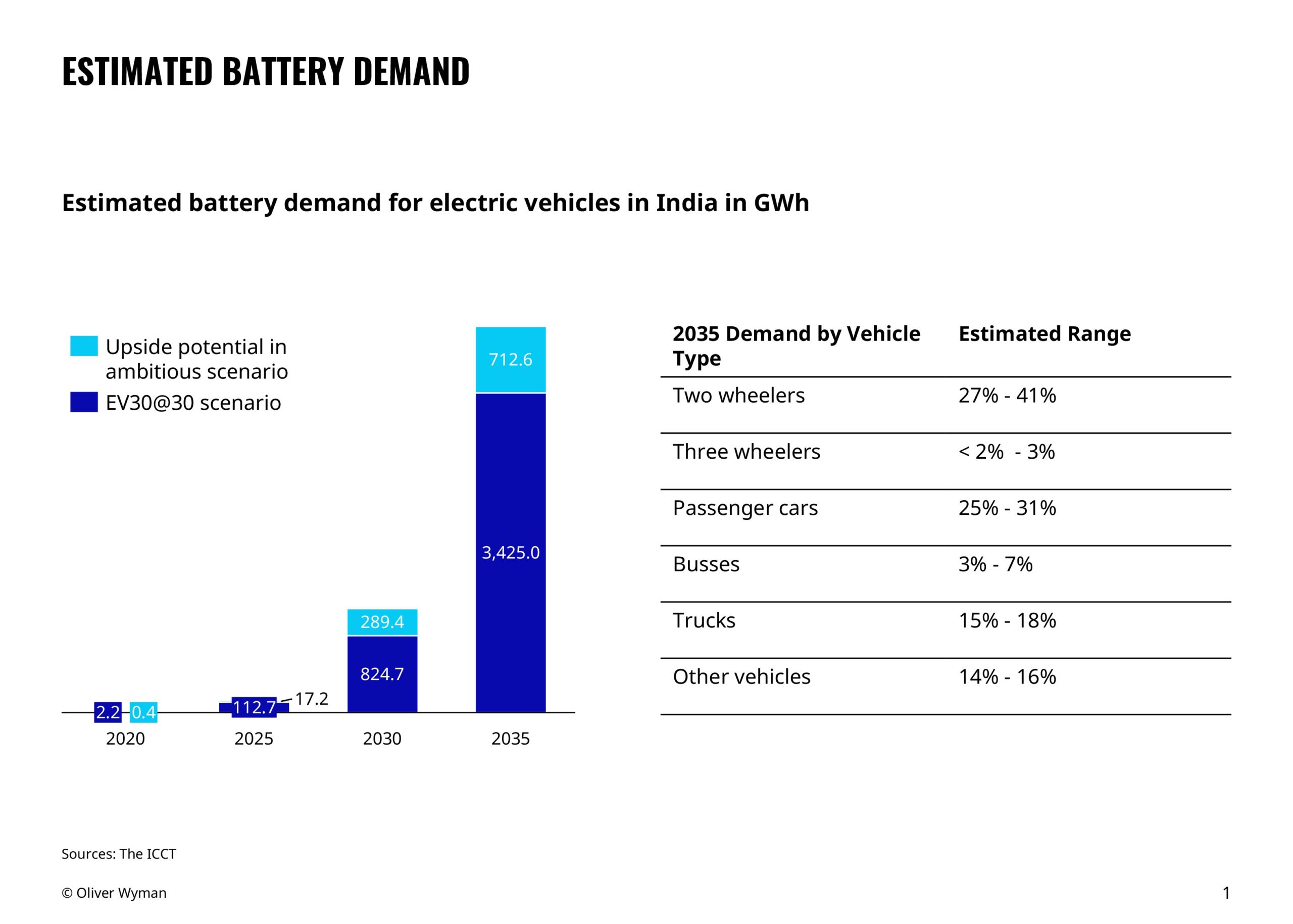

Recently, the International Council on Clean Transportation estimated that to achieve a 30% sales penetration by 2030, India would need over 800 GWh of batteries. A similar number was also touted earlier by NITI Aayog and the Rocky Mountain Institute. It is imperative to establish local cell manufacturing facilities in India to support this scale of transformation for multiple reasons.

First among them is the local value creation perspective. Today, batteries represent 40-50% of the costs in a typical compact class electric car’s bill of materials, compared to ~30-40% costs in case of conventional powertrains. Even though battery prices are dropping globally through scale economies and advancements in product and production technologies, they could still represent about 30% of the costs by 2030. Relying on imported cells would translate to reduced local value creation, as well as a switch in India’s import dependance from oils to batteries. Concurrently, local manufacturing creates jobs, which provides a buffer against those lost in redundant engine, transmission, and component manufacturing plants.

Additionally, local cell manufacturing also has pragmatic considerations. Batteries are heavy and hazardous goods that can get damaged in transportation. This results in complicated and expensive logistics needs. Furthermore, local sourcing helps build supply chain resilience, mitigating potential disruptions and geopolitical risks, while supporting local demand. Adopting a broader view, Indian battery cells leveraging domestic manufacturing competences, factor costs, and geographic location would provide trade and export opportunities. Indian firms could also expand downstream capabilities to recycle cells, thus securing raw material access over the long term for the local gigafactories.

Status Quo in India

Recognizing the need, India is adopting a phased manufacturing approach, starting with localization of pack assembly in the short term, with a view towards local cell production in the long term. A Production Linked Incentive scheme for Advance Chemistry Cell (ACC) Battery to the tune of INR 18100 crore over a five-year period has been approved by the union cabinet in November 2020. Import duties are also expected to play a role in incentivizing sourcing from local manufacturers. Industry players are also actively seeking to engage, with some examples in the news recently of moves along the value chain, as well as announcements from some industrial players looking to set up local plants. Given the nascency of the Indian battery manufacturing landscape, however, there are significant challenges which need to be overcome, and potential opportunities to be exploited. Here, the approaches adopted in other regions offer some valuable insights and lessons on developing local battery industries.

The European Playbook

While South Korean and Japanese players had an early start in the sector, Chinese firms backed by coordinated efforts of their government have catapulted to the forefront of late. They not only lead in terms of installed and announced plant capacities, but also in control over the upstream value chain and in EV sales penetration. Given the strategic importance of battery cells, other regions have scrambled efforts to catch up with these Asian giants.

The most prominent, and successful, example is Europe. Despite its diversity, Europe has studied and adapted the playbook of the Asian players to rapidly establish a local ecosystem. By strongly promoting EVs and putting the focus on decarbonization and sustainability, the demand for batteries was created, inviting battery makers to open factories locally. These have further been supported through financial and regulatory incentives – not only in cell manufacturing, but also from upstream steps like mining and material preparation to end-of-life management. The focus on sustainability is also translated into regulations determining how batteries are manufactured, be it the emphasis on material sourcing practices, using green power in production, or mandatory recycling targets.

While some of the industrial players are adopting a fast follower strategy and forging technology partnerships with established players, the European Commission is also intensively promoting research and development efforts across the value chain into battery and manufacturing technologies. European industrial players and SMEs are also encouraged to participate by transferring and applying their historic strengths and competences into battery manufacturing ecosystems. Data analytics also plays a crucial role – be it through industrial automation and IIoT technologies in production, or the use of AI in intelligent battery management through the lifecycle. These efforts are also supported through a focus on developing and reskilling the workforce, and by ensuring consistency across the various policies and regulatory frameworks.

Potential Indian Solutions

In the spirit of Aatmanirbhar Bharat, there is a strong case for setting up an Indian battery manufacturing ecosystem. In this pursuit, studying the approaches taken by other regions, adapting them to the local context, and marrying them with unique domestic factors is critical. Efforts of policy makers, industry players, and broader stakeholders in the ecosystem must be coordinated for achieving this. In terms of cell manufacturing, the PLI scheme provides a springboard to fast-follower firms and offsets the high capital expenditures needed for setting up a gigafactory. This must be supported with demand side measure to promote EV penetrations with carrots (e.g. tailored incentives for private and fleet buyers, charging infrastructure growth) and sticks (e.g. fuel economy/CO2 standards and EV sales targets for vehicle manufacturers, low pollution zones in cities).

The phased manufacturing strategy targets increasing vertical integration and localization in a stepwise manner. In the short term, Indian players must seek collaborations with global firms along the entire value chain. Securing long-term raw material supplies, especially for critical minerals like lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese, needs urgent efforts and upstream partnerships. Concurrently, Indian OEMs must deeply contemplate which battery cell designs and chemistries are most suitable for local environmental conditions, vehicle specifications, and price-sensitive customer segments. For example, there is a growing consensus that batteries with LFP cathodes are better suited for volume segments and commercial applications, which also attenuates the demand for some critical materials.

At the same time, it is critical to fast-track battery research and development activities, fostering intensive cooperation between local universities and industry firms. Battery design is crucial to control the technical specifications and performance parameters, ensure quality and reliability, and can be a core competitive advantage for OEMs. The abundance of young engineers and scientists in the India can be tapped for leapfrogging in technology solutions as well as deployed in the jobs created while growing the local ecosystem. Indian MSMEs and industrial firms must also pivot to cater to the equipment and component needs created in this process.

Further, India’s strength in information technologies offers potential to develop intelligent solutions for managing batteries from cradle to grave. This would enable better utilization of batteries in first life applications in EVs as well as second life potentially in energy storage solutions. Finally, end-of-life waste management directives and extended producer responsibility norms, coupled with recycling efficiency targets, can help the cell manufacturers proactively design and develop circular business models.

Though there are considerable and multifaceted challenges that need to be addressed, India has started taking the right steps in promoting domestic battery manufacturing. It is imperative to continue building on this through concerted efforts across the entire battery and vehicle value chains to promote the development of an entire local ecosystem together with global partners. The right measures can thus pave the road for accelerating India’s clean energy transition.

—————————————————————————-

Srinath Rengarajan is an Automotive Expert at Oliver Wyman, where he leads the global automotive research team. He is also an Ambassador at Battery Associates and a member of the Executive Committee of the Indo-German Young Leaders Forum. He is a keynote speaker at international battery conferences and has authored multiple articles on electric mobility and batteries.