Shift to electric vehicles can help cut share of transportation in greenhouse gas emissions, states Hetal Gandhi, Director, CRISIL Research

An all-out bid to promote adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) may be just what India needs to achieve its target, or nationally determined contribution (NDC), set under the Paris Agreement it inked in 2015. The central aim of the Paris Agreement was to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by limiting the global temperature rise to 1.50 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100, alongside increasing the ability of countries to deal with the impact of climate change. India is on track on two of the three components of its NDC, to be achieved by 2030. First, against the target of reducing the emissions intensity of GDP by 33-35 per cent by 2030 over the 2005 levels, it has already reduced emissions intensity by 21 per cent.

Second, with 38 per cent of non-fossil fuel capacity that includes renewables, large hydro and nuclear, India is just 2 per cent short of its 2030 target of 40 per cent of installed non-fossil fuel electricity capacity. But on the third component, which requires achieving 2.5-3.0 billion ton carbon dioxide equivalent through addition of forest cover by 2030, much more work is needed. This classifies India in the ‘fair share’ range of 20 degrees Celsius goal of the Paris Agreement as per Climate Action Tracker, but may not be fully consistent with the long-term temperature goal of 1.50 degrees Celsius. Also, in terms of GHG emissions, it may be in the insufficient category based on current projections.

Transportation: Key to Cutting GHG Emissions

Worldwide, the energy sector contributes 73 per cent of GHG emission, with transportation accounting for 7.9 giga ton of equivalent carbon dioxide in 2016, or 15 per cent of total emissions. The share of the energy sector is high in India as well, with transportation having a similar share. Recent reports from the likes of UNEP Emissions Gap 2020 project a shortfall of about 60 per cent in emission between country commitments and progress towards 1.50 degrees Celsius. New Zealand and a number of countries from the European Union are taking huge steps to up their commitments on emission gases. However, for the global goal to be achieved, India has to play a key role as it is the third-largest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2), being the second-most populous country and a high-growth economy.

It has to become more transparent by describing the GHG emissions, sectoral coverage and metrics for target reductions – especially in transportation. Passenger and freight transport use a whopping 96 per cent of the GHG-emitting fossil fuel. Currently, the Indian transportation sector accounts for around half of the total crude oil consumed in the country, with 80 per cent guzzled by road transportation alone. Further, while our per capita transport emissions are nearly one-fourth the G20 average, they have been growing at an alarming clip of 25 per cent a year. The share of low-carbon fuels in the transport fuel mix needs to go up to 60 per cent by 2050.

The Role of EVs

India is in a unique position. Motorisation levels are low in the burgeoning middle-class, indicating significant under-penetration across automotive segments. However, carbonisation levels are high, with the share of transportation in carbon emission nearly doubling over the past decade. Hence, focus on electrifying railways, looking at modal shifts in freight transport and shifting to cleaner fuels will be a priority for India as it drives the agenda to cut GHG emissions over the next decade. While railway electrification is at nearly 71 per cent and may well reach the 100 per cent mark by 2030, the modal shift in freight to rail or other modes of transport is expected to be a gradual process. Of the total freight being transported in the country, only about 25 per cent will take the rail route over the next decade from the current low levels. Implementation of Bharat Stage VI norms can bring down the growth rate of carbon emissions from road transportation.

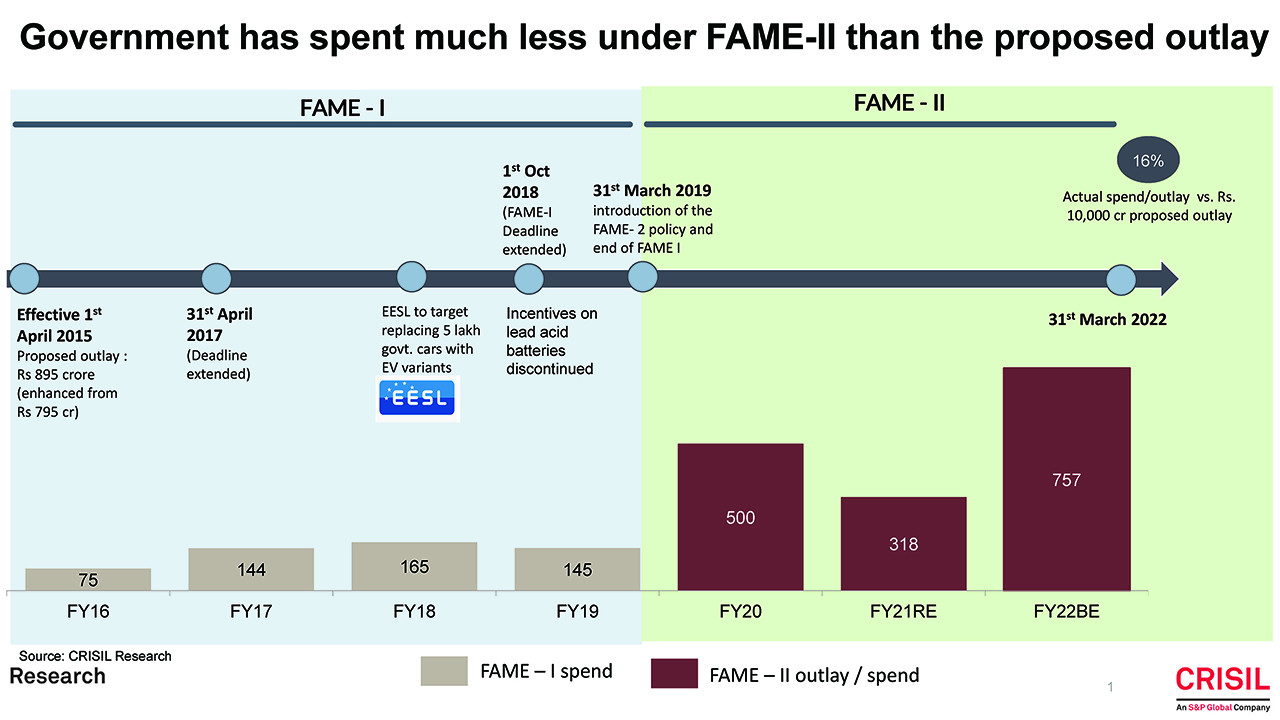

A shift to electric vehicles can, however, lead to a zero-emission status for India directly. Concerns on well-based emissions from coal mining may also be taken care of as the share of renewables rises. But that may be more a reality by 2050 than 2030. The Indian government first announced 100 per cent electrification in transportation by 2030, only to retract it for easier targets given the non-readiness of the ecosystem. The National Electric Mobility Mission 2020 was notified, as were a number of initiatives such as Phase II of the FAME incentives, de-licensing of the charging infrastructure business, and guidelines on battery-swapping business models, along with state-level incentives and EV adoption policies. Latest on the list are production-linked incentives to promote EVs and linked equipment manufacturing in India.

Imperatives for Driving EV Adoption in India

EV adoption in India, or elsewhere, is a function of cost dynamics for the consumer. Acquisition cost and cost of ownership of an EV across most categories remains higher compared with an internal combustion engine vehicle. In segments with higher running such as taxis, where the differential may be lower, weak charging infrastructure, low adoption levels and, hence, best practices for ease of operations are a concern. To break this barrier, most countries have gone for high demand incentives to drive a personal mobility shift to EVs. The Indian government, however, is keen to drive adoption on cost economics. While this has its own positives, such as sustained long-term demand, it may not be enough to push initial adoption.

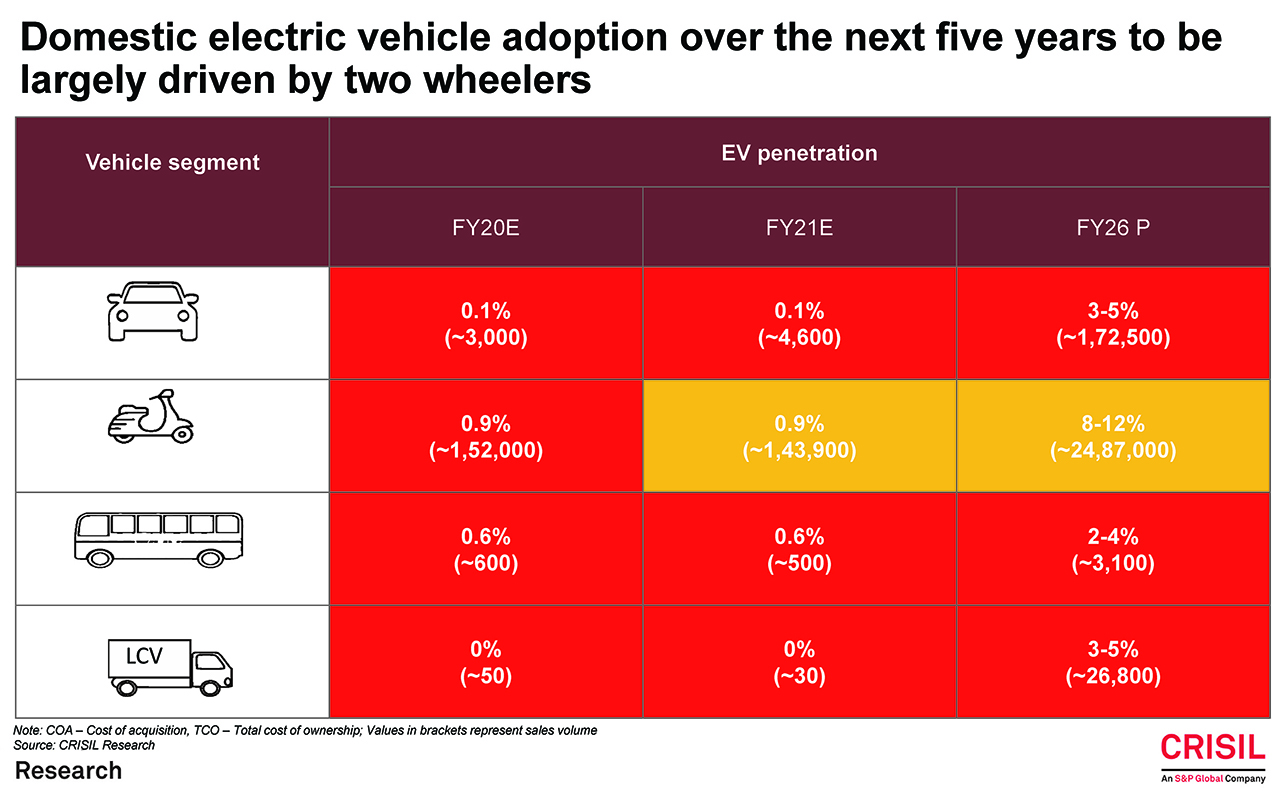

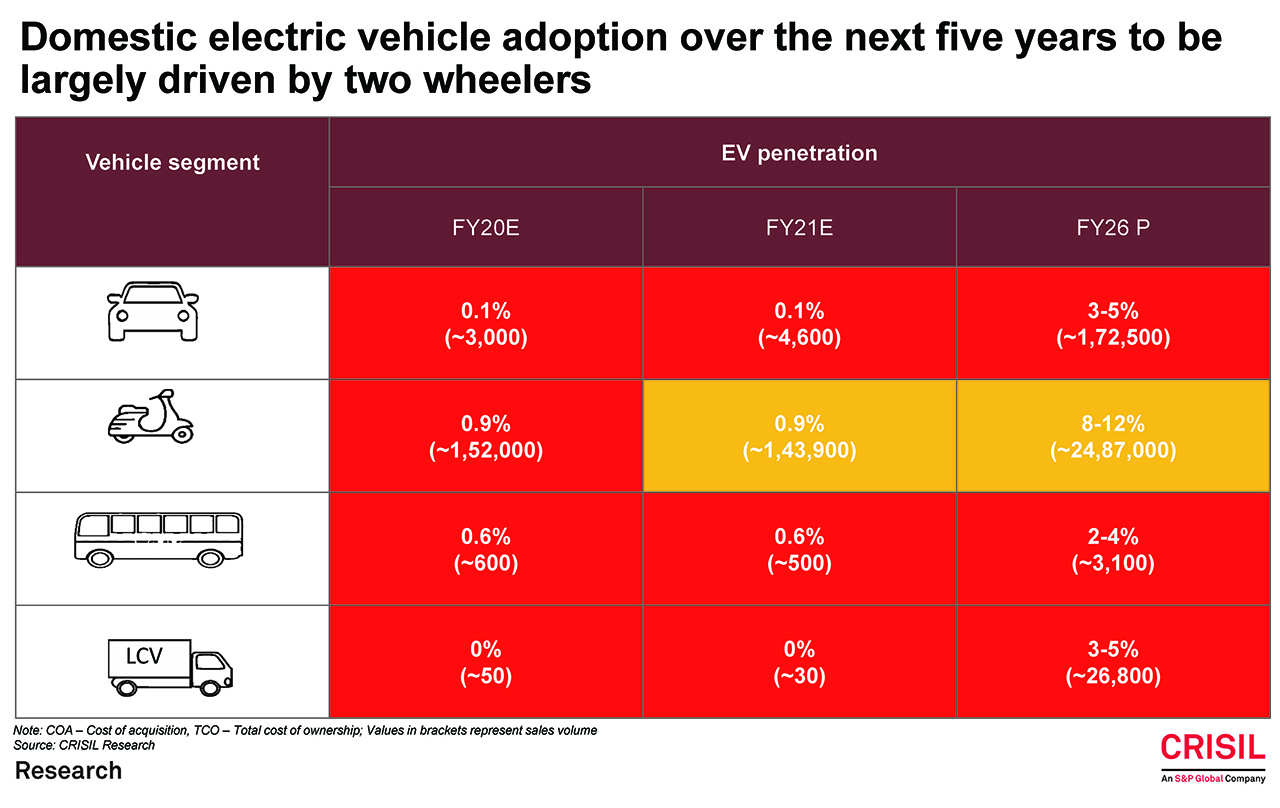

Our best case given minimal subsidy support for direct sales is that by 2025 the maximum EV demand would be from two-wheelers in sheer volumes, followed by three-wheelers. Indeed, as per CRISIL Research estimates, 8-12 per cent of new two-wheeler sales will be EVs by that year. Even this would be an achievement given that there are 15 crore two-wheelers on the road in India, and there would be fresh sales of 2 crore units per year. However, much more needs to be done to raise the EV share in the four-wheeler personal mobility space, where penetration in new sales would be miniscule at less than 5 per cent until 2025. Important in this would be to lower the cost of batteries.

With duties and transportation India’s imported batteries are about 30-35 per cent higher priced than its global counter parts. PLI, if implemented well, could help lower the cost. Further, a stronger push is needed to ensure supply of key raw materials through long-term structural procurement contracts with key nations. The government needs to give an impetus to large-scale battery manufacturing to drive down cost, with localisation targets and incentives linked to phased localisation. Investing in research and development to adopt newer technologies will need to be a focus area, too. EVs could not only help India seize a missed manufacturing opportunity, but could also open doors to innovation though low-cost battery technology. Meeting the Paris Agreement commitments would be a bonus.